Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in the American Maritime Officer, monthly publication of the Seafarers- affiliated AMO. It is reprinted here with permission, and with strong encouragement from the main subject, who comes from an SIU family.

“The SIU holds a very special place in my heart and life,” Fred Reyes said in a recent communication to the Seafarers LOG.

The article has been lightly edited for space considerations.

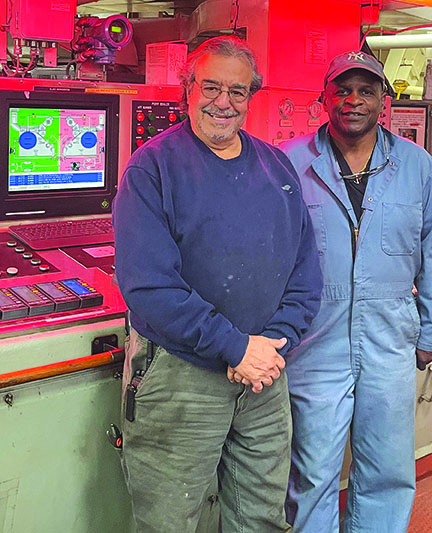

In May of 2023, American Maritime Officers member Frederick Reyes completed his most recent shipboard assignment. He accepted the job to join the S/S Wright in February in Norfolk, Virginia, as first engineer to work on board with a longtime friend: Chief Engineer Sterling Pearson.

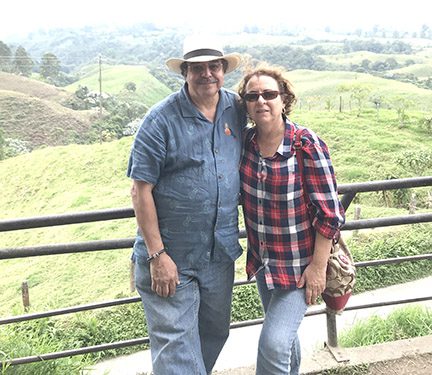

As he walked down the gangway in May, there was a long list of responsibilities awaiting him on the pier, including working with his wife, Nora, to choose their next course of action with the avocado, banana and coffee plantation the Reyes family has established in Colombia in recent years, and deciding whether they should keep all of their horses in the stable or maintain them in the pasture for a few weeks.

Not what you might call standard kitchen-table quandaries, but these are among the interests Reyes has been able to pursue over the years during a long career as a licensed U.S. Merchant Marine officer – working hard, earning well, raising a family and having ample vacation time between shipping assignments.

His rotation on the Wright was the latest installment in a voyage that began 50 years ago in the Bronx, New York.

“I was 20 years old and I was attending Bronx Community College,” Reyes said, noting he had previously attended NYC Food and Maritime Trade High School. “It was difficult to get work. So, I was pretty much a starving student like most students. And my mother says to me: ‘Well, here’s a letter that was given to you when you were born.’ I read the letter. She says: ‘Take this letter to the union (SIU) (which I had been going to in Brooklyn since I was a kid with my father, waiting for him to ship out) and you want to talk to only one person: (SIU President) Paul Hall.’”

“Back then, whatever mom said, you did,” Reyes continued. “I went to Brooklyn, and they usually had the job calls where there used to be a master at arms who would stand in front of the union door entry. So, there was a gentleman named Jack Caffey, who eventually became one of the vice presidents. Jack was the master at arms in front of the union.

“Now, this is 1973, you know. I was a classic long-hair college hippie. And Jack says, ‘What do you want?’ And I’m like, well, I’m here to see Paul Hall. He says, ‘Get out of here, you can’t see Paul Hall.’ And I say, Well, I got a letter here. He read the letter, looked at me, read the letter again, and says, ‘Okay, I’ll be back in five minutes – stay right here.’ He goes inside the building, comes out, and these two men walk out with him. They read the letter, look at me and asked me for ID. I gave them my driver’s license. One of them looks to the other and says, ‘Man, the boss is going to be really happy with this one.’”

Reyes paused in his recollection to point out his full name is Frederick Reyes-Morciglio, and his grandfather on his mother’s side, Francisco Morciglio, was a charter member of the Seafarers International Union in 1938, after having started sailing in 1918. His uncle on his mother’s side was also an SIU member who started sailing in the 1940s, and both of them sailed in the deck department.

Reyes’ father also sailed as a member of the SIU in the deck department, starting perhaps in the late 1930s or early 1940s. He served in the U.S. Merchant Marine during World War II and was later buried in a cemetery for veterans in Puerto Rico. His father had four brothers, and they also sailed with the SIU.

“I think I have salt in my blood,” Reyes said.

When he was born in 1953, the SIU issued Reyes a letter of introduction to the union, stating he could take the letter to any SIU hall in the United States and be recognized as a book member of the Seafarers International Union. He was later informed the SIU had issued approximately 20 such letters in total and had ceased doing so in 1954.

From his encounter with Caffey in front of the hall in Brooklyn, Reyes was escorted upstairs to the dispatching department, led at the time by Port Agent George McCartney, who would later become a vice president with the union.

“George picks up the phone and says, quote, ‘One of the babies just arrived,’” Reyes said. “Then he says: ‘Somebody is going to be here in a few minutes to talk to you.’

“Are you Paul Hall?” Reyes asked. “He says: ‘No, I’m George McCartney.’ I looked at the guy to my right and I asked: Who are you? He says: ‘I’m Mike Sacco (who later became the union’s president).’ Then I asked the guy to my left: Who are you? He says: ‘I’m Joey Sacco (later the union’s executive vice president).’

“Joey grabbed me and says: ‘Man, you don’t know how happy the boss is going to be to see you.’

“Then I started hearing whispers. I’m standing, looking at the counter, and I feel a presence behind me and smell cigar smoke. I turned around and there’s this white-haired gentleman, a little taller than I am, and he takes his stogie and hands it to someone, and this gentleman proceeds to grab me in a bear hug and starts bouncing me. And he says: ‘I’ve waited for 20 years for one of you guys to show up!’

“He finally puts me down and I says to him, Are you Paul Hall? He says, ‘Yes, I am.’

“Good, because my mom told me to talk to you!”

“He says: ‘What do you need, son?’ I told him I want to go on a ship. I want to go to work,” Reyes said. “He looks at Mike and Joey and says: ‘You see this kid? This is family. We’ll always take care of this man.’

“Here it is, 50 years later, and I’m still here,” Reyes said.

Hall gave instructions to have Reyes sent to Piney Point, Maryland, for training before his first shipboard assignment.

“I says to George McCartney, Don’t you have a school here in Brooklyn or Manhattan or the Bronx? He said, ‘No, it’s in Maryland.’

“I don’t have money to get to Maryland. How am I going to get to Maryland?” Reyes said. “In all honesty, George goes into his pocket and pulls out a hundred-dollar-bill, and says: ‘I never want you to be without money again. We’re going put you to work and you’re always going to have money and you’re going to have a good future.’

“Mike says, ‘Look, Freddie, we’re going to be down in Piney Point in about two weeks and we’ll be down there when you get there, so you’re not going to be alone.’

“Are you sure?” Reyes asked. “Joey grabbed me and says: ‘We’re going to be friends forever.’” Reyes attended Piney Point for 12 weeks and left for his first shipboard assignment. “My very first ship was the Sealand McLean, which was a brand-new SL7,” he remembered. His first job was in the steward department taking care of the forward house.

“We set sail from Port Elizabeth and got to the Verrazano Bridge, and the movement of the ship – I got seasick the minute we passed by the Statue of Liberty,” Reyes said. “Back then, they used to make the run from New Jersey to Rotterdam in four days. I was sick the whole trip over and I was sick the whole trip back. I got off that ship 11 days later and said, I quit. I’m not going on another ship.

“I had money in my pocket and I went home,” he said. “I hung out for a couple of days. My mom asked me how the trip was, my uncle asked me how the trip was, and I saw my grandfather. I said, Man, I’m not going out there. This was wintertime, so I had my first ship crossing the Atlantic – a superfast ship that was moving all over the place. Yeah, I was sick.

“My grandfather says, ‘You are going back out there, now!’ So I went back to the union hall and grabbed another ship, and that was the Elizabethport,” another Sealand Service, Inc. ship. “That’s how my career started,” Reyes said.

“When we were crossing the Atlantic, I was getting sick all over the place,” he said. “I thought I wanted to be a bosun or captain. I wanted to be in the deck department. I’d go down to the engine room, and when I went down to the engine room, because it’s a low point of gravity down there, I’d be comfortable. That’s how my engineering career started – I’d go down to the engine room because I didn’t feel seasick down there.”

Reyes took one more shot at a career in the deck department, signing on as an ordinary seaman on a Jones Act tanker running from New York to Texas. He found himself getting bored standing the bow watch the entire trip. The next job he took, he signed on as a wiper and never sailed outside the engine department again.

A few years later, Reyes returned to Piney Point to complete the required seniority program training to earn his A-seniority book with the SIU. This entailed a week or two of classes at the school followed by a week or two in New York going to the morning production meetings with Paul Hall and Vice President Angus “Red” Campbell, he said.

“Red knew my father and my grandfather, so I had a lot of camaraderie there. During one of the morning meetings – there were four of us – it was (current SIU Executive Vice President) Augie Tellez, (current Vice President West Coast) Nick Marrone and two others….

Reyes sailed with the SIU for several years. He would typically sail for five or six months at a time, come home for a few weeks, and after routine prodding from his grandfather, would turn around and go back to sea.

By 1979, Reyes had earned a license. But his introduction to working as an engineering officer commenced well before he sat for the exams.

A few years earlier, he was assigned to attend a new course at Piney Point to qualify to sail on LNG carriers. He ended up working as a pumpman aboard three such ships coming out of the shipyard. He continued sailing on LNG carriers as a QMED, and with guidance from the engineering officers sailing aboard the ships – represented at that time by District 1 MEBA – learned a great deal about the roles and responsibilities of a marine engineer.

“By the time I got a license, I was still sailing on an LNG ship in the capacity of a QMED,” Reyes said. “I got off that ship, went home for a few weeks, then jumped on an AMO ship as a third engineer.”

Reyes had gotten married in 1980 and was living in Daytona Beach with his wife and their one-year-old child when, in 1983, he was contacted by American Maritime Officers (at that time District 2 MEBA) regarding that first job as a third engineer aboard the Cove Trader.

He continued sailing both licensed and unlicensed in alternating voyages, returning to the LNG fleet between AMO job assignments to earn as much money as he could. “For two or three years, I was sailing as a QMED and as an engineer. I don’t know if you can do that anymore,” Reyes said.

Reyes paused for a moment to identify both the captain of the Cove Trader, the late John “Black Jack” Flanagan, and the chief engineer, Alfred “Rocky” Miliano, with whom he still maintains a close friendship. Reyes also remembered meeting STAR Center Director of Training Jerry Pannell, who was sailing as a junior deck officer on the Cove Trader at the time.

“Sailing back then was different,” Reyes said. “There was a lot of camaraderie – in the crew and in the officer ranks. There wasn’t a lot of communication, so we were mariners on a ship in the middle of the ocean.

“It’s a whole new generation of mariners now. There’s a different level of sophistication. The technology onboard the vessels – it’s strictly business now. There’s nothing wrong with it, but it is different. “It’s been a great life voyage for me, personally, being a mariner – being in the crew, and I’ve been an officer for quite a few decades,” Reyes said. “I really care for the crew. I make sure to look after them….

Reyes also reflected upon a situation which stemmed from the sealift operation during the first Gulf War – after Iraq invaded Kuwait – and identified a reality faced by the U.S. maritime industry to this day.

“I was on the Cornhusker State. I was second engineer. We get to Saudi Arabia … and I was standing on the dock and there was a bunch of young soldiers there. One of them asked if I was CIA, because I was dressed in civvies, and I was, like, no. He says, ‘Well, what are you doing here?’

“I came on the ship,” Reyes said. “I’m a merchant mariner. Then I pointed to the ship and said, How do you think the war machine got from the United States to here? And he says, ‘The Navy.’ And I said no, the Navy are warriors. We are the civilian mariners who support you, the combatant. You see those helicopters coming off that ship? How do you think they got here?

“Now I had their full attention and I explained it to them,” Reyes said. “Most people, most Americans, really don’t understand what the Merchant Marine is and what we do.

“For me, going to sea is part of the fabric of my existence,” he said. “Whether it be alongside a dock or crossing the oceans, that’s what I do. I was born to do that and I’m very proud of it.

“I appreciate and I love the SIU for providing the vehicle for me to have this wonderful life as a mariner, and I appreciate the AMO as an organization for taking care of me and my family,” Reyes said. “We as mariners are a certain breed of human being who do what we do.”

Reyes addressed a final point to the next generation of the U.S. Merchant Marine, both junior officers coming out of the academies and hawsepipers beginning their careers as unlicensed mariners.

“Within this industry, you can start at the bottom and work your way up to the top. And it’s possible to do it, because I did it,” Reyes said. “I’m very thankful that going to sea has given me a great life. Because I’ve had a ball.”

###

Comments are closed.