Aside from the obviously not-so-small detail about his miraculous survival for two-plus hours in freezing ocean water, the story of former Seafarer Dick Burbine, 95, isn’t radically different from those of his fellow World War II merchant mariners.

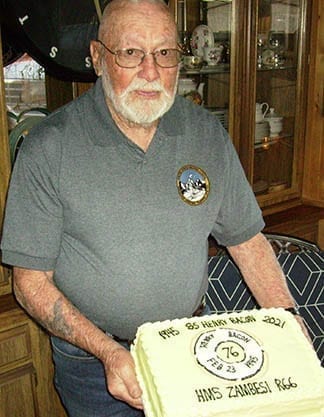

Former Seafarer Dick Burbine, 95, is the last living survivor of the SS Henry Bacon’s final crew. He still celebrates being rescued from the 1945 sinking on the Murmansk Run.

At age 16, eager to help with the war effort, he walked into a Marine Corps recruiting office in Boston in 1942 and tried to enlist, despite the concerned objections expressed by his mother.

But colorblindness prevented Burbine from joining the armed forces.

“They told me to go across the street to the U.S. Maritime Commission,” he recently recalled. “That’s how it came about.”

Other mariners from that era have half-jokingly said the standard for entry into the U.S. Merchant Marine during the war consisted of the ability to fog a mirror. While it may not have been quite that lax, history has borne out that innumerable mariners followed a course similar to Burbine’s. They tried to sign up for military service but were rejected for medical reasons. They could have stayed home. They didn’t.

Burbine, the last surviving member of the ill-fated, SIU-crewed Henry Bacon, shares another trait with World War II mariners in that he knows they didn’t get the credit they deserved for decades following the battle. And, like his seafaring brethren, he still finds it bothersome – not because any of them craved attention, but because of basic fairness.

“I’m insignificant,” said Burbine, who lives in California, near the Nevada border, and still leads an active life. “My objective with this story is, the merchant marine has never been given the recognition that they should have. They were the best. They all went back on their own. They believed in the cause, and to me, that is the finest thing in the world a person can do.”

Many returned to sea after surviving a sinking. Burbine is one of them.

Dangerous Waters

The hardiness of the U.S. Merchant Marine of World War II simply isn’t debatable. Depending on who does the math, they suffered a casualty rate that either exceeded any of the armed forces or was second to that of the Marine Corps. They often sailed with minimal protection, if any. They indeed were an all-volunteer service. More than 8,000 of them died at sea; another 11,000 were wounded.

But the surest way to make one of the surviving mariners cringe is to say the words, “Murmansk Run.”

Infamous for its foreboding conditions, the Murmansk Run partly consisted of a dangerous Arctic Ocean passage from Iceland or Scotland to northern Russia. U.S. vessels joined those convoys beginning in 1942, sending a total of approximately 350 ships during a three-year stretch. Nearly 100 of those vessels were sunk by Germans, and thousands of Americans aboard them lost their lives.

The Liberty Ship Henry Bacon, operated by South Atlantic Steamship Company, safely arrived in Murmansk in February 1945, delivering war materials and other supplies. Wiper Dick Burbine, having just turned 18, was one of 40 crew members. The ship also carried 26 members of the Navy Armed Guard.

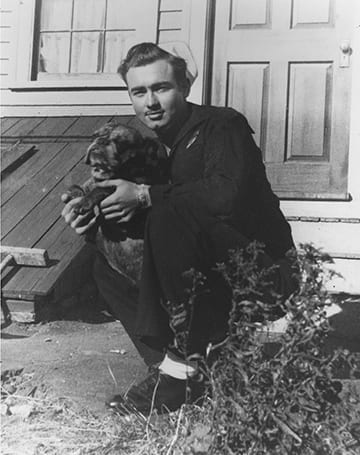

Burbine in 1945

The Bacon took on more personnel in Murmansk. The British Navy had rescued more than 500 Norwegian civilians from occupied Norway and moved them to Russia. Nineteen of the refugees, most of them women and children, were assigned to the SIU-crewed ship, for transport to England.

They’d make regrettable history, as the Bacon became the last Allied vessel sunk by German aircraft.

Upon leaving Murmansk on Feb. 17, the Bacon was part of a convoy that included 35 ships and naval escorts. But a combination of severe weather and mechanical problems causes the Bacon to stray, and because of radio-silence protocols, they couldn’t alert the other vessels.

On Feb. 23, more than a dozen German aircraft (torpedo bombers) found the Bacon some 60 miles from the convoy, mainly because of damage to the steering engine. Gunners aboard the merchant vessel shot down at least five of the airplanes and damaged four others, but eventually the Bacon succumbed to a torpedo, striking the #5 hold.

Following orders, Burbine was readying what apparently was the ship’s only viable lifeboat when a second torpedo hit.

“The other davits were frozen solid,” he recalled. “The lashing lines were frozen. The chief engineer told me to get in and cut the lashings. When we got hit, the lifeboat went over the side with me in it. When I came to, I was under it, in the water. That’s the one we eventually used for the Norwegians. I was the first one in the water and the last one to be picked up.”

Survivors

In 2021, Burbine’s rugged appearance, sharp memory and volunteer work in forestry (often including use of gas-powered chainsaws) undoubtedly seem improbable for someone his age.

Then again, perhaps longevity was a given after what he and some of his shipmates somehow survived as the Bacon went under.

The temperature was around 40 below zero, with high winds. Shortly after the Bacon sank, Burbine rounded up two other mariners and an armed guard member and assisted them with life rings. They never left the water until a couple of hours later, when three British destroyers arrived just before nightfall.

Although many of those who made it off of the ship died in the waters from hypothermia, Burbine and his immediate comrades pulled through, as did all 19 refugees and others who boarded a second lifeboat. The attack claimed the lives of 16 mariners and 12 armed-guard personnel.

“The only thing I said was, I’m not going to give up,” he said. “God helped me and that was it. My whole intention was I’m not going to give up.”

Burbine remembers “people hollering, looking for help. I remember swimming in a life ring. The winds were blowing, and we were down low in the water. At one point and ice cone blew over us, and I’m certain that helped.”

Eventually, he and many others were pulled to the deck of the British Zambesi, then taken to the crew mess to thaw. What followed, despite the dire circumstances, might qualify for a comedic movie scene, or at least a quirky one.

“They had no medication,” Burbine stated. “The ship’s doctor said, ‘I don’t have any medicine, but I’ve got all the rum you can consume.’ It worked. I never lost any extremities or anything, and to this day, I still drink rum once a week or so.”

Another twist awaited, though. Some of the survivors were taken to a castle in Northern Ireland and were “interviewed by every service they had,” Burbine said. “They thought we were German plants, because no one had previously survived that long in those waters. They interviewed us for eight hours.”

Once cleared, they were transferred to Glasgow, Scotland, for two weeks, then were sent back to the United States aboard the USS Wakefield.

“We returned to Norfolk (Virginia) and were told we were free to go,” Burbine said. “That was it. No ‘thank you,’ no nothing.”

He continued recuperating for a couple of weeks, then shipped out again, aboard an Ore Steamship vessel.

More Adventures

Burbine’s maritime career began with a voyage aboard the National Maritime Union ship Sea Marlin, which sailed to numerous Pacific islands. Upon returning to the U.S., though, he joined the SIU in Norfolk.

“The SIU was the best union I ever belonged to,” he said. “I have nothing but good feelings and thoughts for them. They were good people and they treated you fair and square.”

He thought highly enough of the SIU that he rejoined it after finally being accepted in the Marine Corps in 1950. He served three tours in Korea during the war, mostly as part of VMO-6, a helicopter observation and rescue squadron.

“That was 32 months of solid combat,” Burbine remembered. “We did over 7,000 Class ‘A’ evacuations.”

But after nine years in the military, he returned to the SIU and resumed sailing until 1965 (always as part of the engine department). He eventually transitioned to a career in law enforcement, then, after retiring, began volunteering with a forest service in 1988.

Regarding his maritime experience, Burbine said, “I still feel I’d do it all over again. I’ve been all over the world, and I was fortunate because I enjoyed what I was doing. I would even do the Murmansk Run again, under the same conditions.”

He said he considers his entire career a highlight, but mentioned a chance meeting with then- SIU President Paul Hall in New York as a moment that stands out. “It wasn’t exactly like royalty, but he was an executive-type individual,” Burbine said. “But he was also down to earth. He was a seaman at heart.”

‘Nothing But Pride’

Burbine always commemorates the anniversary of the Henry Bacon rescue. For decades, he kept in touch with other survivors. The last of them passed away in 2020.

Burbine endures, as does his frustration that history sometimes overlooked the wartime service of civilian mariners.

When President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the GI Bill in 1944, he said, “I trust Congress will soon provide similar opportunities to members of the merchant marine who have risked their lives time and time again during war for the welfare of their country.”

No such action took place. World War II mariners eventually received veterans’ status in 1988 (it took another 10 years before the cutoff date for such recognition was extended to match the one used for the armed services). By then, however, the distinction proved more ceremonial than practical.

Other wins have been secured, though. The U.S. Merchant Marine is included in the World War II Memorial in the nation’s capital. Last year, the president signed the Merchant Mariners of World War II Congressional Gold Medal Act. Physical memorials exist across the country. Books have been published that focus on their contributions. High-ranking military and government officials in recent years have made extra efforts around National Maritime Day (May 22) to salute the service of mariners from that era.

For his part, Burbine simply wants the public to know the truth about him and his shipmates. “There was not one merchant mariner in the whole system that didn’t volunteer for it,” he stated. “General (Dwight) Eisenhower said, ‘When final victory is ours, there is no organization that will share its credit more deservedly than the U.S. Merchant Marine.’ I firmly agree with him. The U.S. Merchant Marine is still one of the finest organizations that served our country during the war. They were outstanding people for the simple reason that they wanted to be there. I always admired that about each and every one of them, and I have nothing but pride for the U.S. Merchant Marine.”

###

Comments are closed.