Editor’s note: This is the final installment from a 1951 booklet titled “The Seafarers in World War II.” Penned by the late SIU historian John Bunker, the publication recapped SIU members’ service in the War. More than 1,200 SIU members lost their lives to wartime service in the U.S. Merchant Marine. Earlier segments are available on the SIU website and in print beginning with the May 2020 edition of the LOG. A PDF of the entire booklet is on the SIU website (navigate to the “SIU and Maritime History Page” for that link). This last section picks up as the author describes the plight of crews who made it into lifeboats after their respective vessels were sunk. First up: mariners from the new Liberty ship SS James W. Denver, bound for North Africa on April 11, 1943 when it was torpedoed and sunk.

They all looked around to see if the sub was going to surface and spray them with machine gun fire, for such a possibility was in the minds of all torpedoed men during the war. But the U-boat never showed itself – not even coming up for an inspection of its kill.

Deck Engineer Dolar Stone tells about the 34-day odyssey taken by the 18 men in his boat after the survivors separated that night.

“There was a little half-hearted joking at first,” he recalls, “but, all in all, it was a pretty solemn affair. We hated to lose our ship, and to see her go down without even having fired a shot in defense.”

The Skipper gave them a course to steer, and told each boat to “hoist sail and get going.… The sooner we sail, the sooner we’ll land.”

Dolar’s boat stepped its mast, hoisted the little red sail with which Liberty ship lifeboats were equipped, and set out for the east. Seas were making up fast under a sharpening wind, and they soon had to rig a sea anchor and heave-to before the waves. The other boats by this time were out of sight and they rode the sea alone, a tiny flotsam, so it seemed, on that huge expanse of darkening ocean and breaking white caps.

A lifeboat in placid waters is anything but comfortable, and the keelless craft pitched, rolled and wallowed all that first night and for the day and night that followed, making all hands wet and miserably seasick.

Just at dusk on the third night, the lookout stationed in the bow sighted a vague shape looming up ahead, and in the excitement of this discovery yelled, “Destroyer!” As soon as the lookout had sung out, Dolar lit the boat’s lantern and, standing up on the bow thwart with one hand on the mast, waved it back and forth as a signal, on the chance that the ship would see them, if indeed there was one up ahead.

To better attract attention, each man switched on the little lights that were fastened to a pin and lanyard onto their lifejackets, hoping that the red glow would shine enough to be seen through the night.

And then, before they realized what was happening, a shape loomed up directly in their path – the black hulk of a submarine.

“It was a big one,” say Dolar, “and we were headed right for it.”

While they watched the raider in amazement, the lifeboat grated against the submersible’s hull, sheering off just in time to keep from riding right onto the low flying deck. One of the U-boat’s officers shouted at them from the conning tower.

“What ship are you from?”

They knew it was no use to evade the query, for the Germans could inspect the lifeboat and find out anyway.

“Denver,” they replied, “the James W. Denver.”

The men on the conning tower had a good laugh over the fact and the SIU men guessed that this must have been the sub which sank them.

“Well,” the German answered in good English, “so you lads are from one of those Liberty Ships.”

The remark sounded sarcastic, but before the sub moved off into the darkness a sailor came down the deck to hand them a carton of cigarettes and from the bridge the officer shouted a course for them to steer. During the next hour they sighted two more U-boats, evidently part of a wolf pack.

Rough Seas

All hands continued to be seasick as the heavy weather persisted, and the lifeboat made more mileage up and down than it did toward the east.

Rations got low after the first 12 days, crackers gave out, water was limited to three ounces a day per man and there was nothing left to eat but malted milk tablets. Three flying fish landed in the boat most opportunely and were cut up in equal parts to be eaten raw. It was not the first time that these airy fish helped to sustain torpedoed crews!

On the night of May 11, the sea-tossed survivors saw moving lights some distance off. These immediately disappeared when the men shot flares. “Probably more subs,” Dolar believes.

Just three days later, however, the long voyage ended. Spanish fishermen sighted the boat, picked them up and took them to La Aguera in the Canary Islands, from whence they later got passage back to the States by way of Cadiz.

After the torpedoing, the Captain’s boat had set a course for the nearest land, which the Skipper figured to be Rio del Oro on the coast of Africa.

For the first 12 days, things weren’t so bad. At least there were crackers to munch on and some of the sickeningly sweet pemmican which had been devised for lifeboat crews. But on the thirteenth day the food gave out and from then on it was nothing but water. Even at that, the water was limited to three ounces a day per man.

The winds held strong, which was a blessing, but it also made life uncomfortable, throwing spray over them continually for each of the 25 days they were adrift. At night it was cold and, being thoroughly wet, they almost froze before the sun broke across the seas each morning.

Captain Staley had a sextant but this was of no use without the necessary tables to go with it, so he relied on dead reckoning while the helmsmen steered with a compass between their legs. When the food ran out, the men became discouraged and from time to time some of them had to be restrained from jumping overboard, for they dreaded the prospect of becoming crazed from sun and salt spray.

Every once in a while, someone struck up a song and they all joined in. When the water was doled out the Skipper would say, “It may be water now, but keep your spirits up and it’ll be juicy steaks one of these days.”

The songs and the promise of steaks – it helped to buoy their spirits, make them forget somewhat the discomfort, the hunger and the monotony.

Finally, they saw fish spawn in the water, a sure sign that they were coming into shallower depths. This was followed by gradual changing of the sea from blue to green as they entered the 100-fathom curve. Their hopes soared, for they knew now that the shore wasn’t too far off.

On the 5th of May they sighted land and, with the wind still holding good, sailed right up on to the sands of Rio del Oro.

By this time, none of them could walk and they tumbled out of the boat like so many cripples to crawl across the welcome sands on their hands and knees. For a while they exulted in the luxury of just being on dry land, but this joy was tempered when they discovered that all around them was a vast desert – nothing but dunes and endless sand. There was no habitation or sign of life anywhere-not even a tree.

At night there were terrific sandstorms and during the day the blinding sun.

They might have died there on the sands of Rio del Oro and never been found if it hadn’t been, strangely enough, for a German submarine which had been sighted and depth charged by British patrol planes, not far offshore from the spot where they had landed just a few days before.

On the 10th of May, five days after the weak and hungry men had beached their boat on the African coast, these planes were out searching for the U-boat and sighted the Denver’s men sprawled about on the sand.

Not many hours later a patrol vessel came by and landed a party armed to the teeth with revolvers and rifles, for they thought the men from the Denver were survivors from the hunted U-boat.

It is a tribute to the hardihood of these SIU men and the Navy armed guard gunners that all survived the ordeal and went back to sea after reaching the States some weeks later.

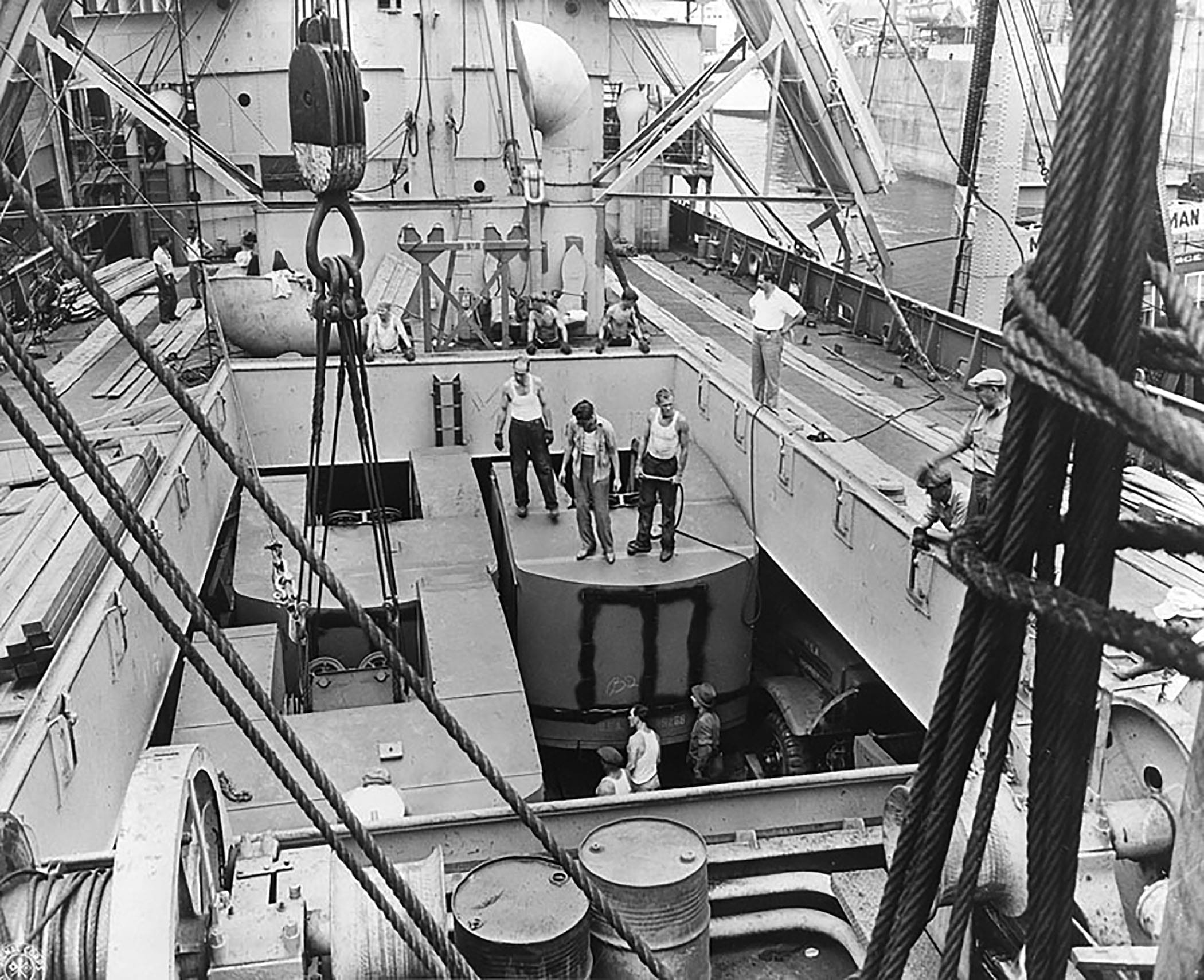

Mariners load materiel into the hold of an unidentified cargo ship in New York Harbor,

September 1944.

The Fighting Henry Bacon

No better finale to the story of SIU ships in World War II could be written than the epic account of the SS Henry Bacon, an SIU-manned Liberty operated by the South Atlantic Steamship Company.

Cold were the Arctic waters and forbidding was the sky when the Henry Bacon added its name to the list of valiant fighting freighters.

Besides her crew, the Henry Bacon carried 19 Norwegian refugees as passengers, when she headed back toward Scotland after a voyage to Murmansk, North Russia, in the early winter of 1945.

After leaving the White Sea, the Bacon had been in convoy, only to lose contact with it on the 19th of February because of heavy weather. She rejoined it on the 20th, then dropped out again two days later when trouble developed with the steering gear. A heavy gale was blowing, and Captain Alfred Carini radioed his plight to the convoy while the black gang worked on the steering mechanism.

Contact Lost

With this finally fixed, the Bacon proceeded, meeting up with more moderate seas. But, seeing no sign of her companions, Captain Carini then decided they must have passed during the night as they hurried to rejoin the fleet. Having lost radio contact, and there being no response to his messages, he decided to turn back over his course for just one hour in the hope of picking up their companion ships.

It was while doubling back on her wake that the Henry Bacon was suddenly attacked by a huge flight of 23 torpedo planes that pounced upon the lone Liberty almost as soon as the thundering roar of their engines was heard through the leaden sky, sending the crew running to battle stations.

Twenty-three planes against one merchant ship! It was odds enough for a battleship or a cruiser. Many a big aircraft carrier that thought itself hard pressed in the Pacific thundered back at half as much opposition with a hundred times the firepower that this unattended freighter could muster for its defense there amid the bleak, rolling waters. There was not another ship around upon which to call for help.

The bombers were Junkers 88s, coming in off the starboard bow in an extended, wing-to-wing formation no more than 30 feet above the jumbled wave tops.

All Guns Working

Every gun on the Bacon went into action as soon as the canvas covers could be jerked off the barrels, and the magazines clamped onto the breech of the 20-millimeters. The sky around the ship was pocked with shell bursts as the fighting merchantmen and the vessel’s armed guard drove off sally after sally by those audacious bombers that attacked simultaneously, one to a side, darting away through a hail of 20-millimeter shells.

The gun on the bow boomed out at point blank range, blowing one bomber to pieces as it banked and exposed its belly to the Bacon’s forward gun. Another Nazi nosed into a wall of 20-millimeter fire and dived into the sea in flames. A third wobbled aimlessly over the waves with smoke pouring from his engine. He probably crashed into the steep, green seas soon after, but the crew had no time to worry about verifying their hits.

When the Germans swooped down on the unaccompanied Bacon they probably were expecting an easy time of it. Three or four torpedoes and the laboring Liberty would sink beneath the waves, they no doubt thought. If they expected any resistance at all, they were certainly unprepared for the flame and fire of battle with which the men of the Bacon met this overpowering assault.

More Ammunition

The 20-millimeters stopped firing long enough only to load more ammunition, to change over-heated barrels. A bomber which tried to get in at the ship from dead ahead ran into a storm of this small shellfire and disintegrated into a thousand pieces, as tracers found the torpedo slung beneath the fuselage and blew up plane and occupants in a terrible explosion of steel and flaming debris.

Torpedo after torpedo missed the ship when the pilots faltered in their aim in the face of such concentrated fire form this fighting Liberty. For 20 minutes the gunners of the Henry Bacon, standing side by side with the men of the merchant crew, held off this armada of Junkers bombers that had by now become so madly exasperated by the heroic defense of the ship that, once their torpedoes were wasted, they flew at her with machine guns blazing.

But such a fleet of planes had only to persist, if nothing else, to be successful against one unescorted ship, and a torpedo finally hit the Henry Bacon on the starboard side in number-three hold, forward. When another tin fish found its mark soon after, Captain Carini ordered the ship to be abandoned.

Not All Leave

The fateful signal to “leave her” was sounded in long, solemn blasts from the whistle while the Junkers – about eight or nine fewer than when they had begun the fight – roared away from the scene toward to coast of Norway 200 miles to the east. The doughty Bacon had kept them in action longer than they wanted.

With their gas getting low, they could find no satisfaction in winging around as this “bulldog” settled beneath the waves.

The order form the Skipper was “passengers first” and, though two of the lifeboats had been smashed in high seas, the Norwegian refugees – men, women and children – were put safely over the side into the first boat launched, along with some of the merchant crew and Navy gunners. Into the second lifeboat went as many more as could be accommodated. It could not possibly hold them all, but still there was no rush for seats of safety. These SIU crewmen and their Navy comrades waited quietly as Third Mate Joseph Scott counted the regular crew assigned to the boat, and then called to the deck above for half a dozen more to climb down over the scramble nets and take their places between the thwarts.

During this time Bosun Holcomb Lemmon was making what the survivors later described as “heroic efforts” to help his shipmates over the side into lifeboats and onto several life rafts which had been launched into the chilling waters. This done, he hurried about the sinking ship gathering boards to lash together as emergency rafts.

The Henry Bacon was slowly sinking. Water was pouring into her holds. The black gang had left the engine room and all was deserted down below. Bit by bit the cold water rose higher around her rust-streaked side plates.

One of the men assigned to a place in the Third Mate’s boat was Chief Engineer Donald Haviland, who climbed over the side into the bobbing craft only to decline his chance for rescue in favor of a young crewman. The Chief had already taken a seat in the boat when, looking up at the men still left on the Bacon’s deck, he saw among the forlorn group a youthful crewman staring down at those who were about to push away from the settling hulk.

Deserting his own place on the boat, Mr. Haviland yelled to the lad to hurry down the net and take his chance for safety.

So Long, Brothers

“Hey, you,” he called. “You’re a young fellow. It won’t matter so much if I don’t get back.”

As the Henry Bacon went down, the survivors in the lifeboats saw Chief Engineer Haviland leaning against the bulwarks with Bosun Holcomb Lemmon, as casually as though the ship was leaving the dock for another routine voyage. Captain Carini waved to them from the bridge and, as he did so, the Henry Bacon slid swiftly and quietly under the sea.

A big wave rolled over the spot and soon only some floating board and crates marked where this gallant fighting freighter of the SIU had written such a glorious chapter into the annals of the American merchant service.

###

Comments are closed.